A few years ago, our CEO gave a talk about copywriting in London. We've decided to share the video and transcript. It's a powerful insight into the copywriter secrets we use at Articulate to help our clients express themselves.

Introduction

I am Matthew Stibbe, and I run a company called Articulate Marketing. We do copywriting for various companies such as Microsoft and Microsoft partners. I’m going to use Apple examples today though!

Some issues this talk will cover:

- To learn how to speak to the real world without sounding completely stupid.

- Avoid using so many clichés when writing e-mails, etc.

- How to move people to action.

- Dealing with the tidal wave on information.

So, it's about cutting through the noise, right? It's getting your message across. Useful, if you're an acting person and you want to get seen; if you're a business and you want people to take action; if you're writing an e-mail and you want people to pay attention and do what you say.

The enemy is the phrase TL;DR, which means ‘Too Long; Didn’t Read.’ (note, this transcript is for a 75 minute-long video, but we promise it’s a worthwhile read!)

This is our lives, right? A constant tidal wave of information. So, if you're writing, you've got to get through that noise, get people to understand, pay attention, listen, believe, take action.

The other problem that we have is shrinking attention spans, or perhaps overloaded attention. People expect information to be dropped in. It’s like the trend on TV shows where they spend the first five minutes at the beginning telling you what's going to come up, and then there's an advert break, and then they spend five minutes telling you what they just told you and what's coming up in the next bit. Half the programme is just kind of repeating itself because you can't pay attention.

People want everything summarised down to a little perfect little one word. This is the challenge that we have.

The science of reading

Let’s start with a bit of science. You think your experience of reading as a human brain is something that smooth and continuous, and left to right and top to bottom, in English anyway. In the same way that when you go to the movies, you think it's animated. People seem to be running around and Superman's jumping from building to building, but actually, it's just 24 frames per second of light flashing on a screen. Your brain does the work. Your brain is actually putting that together from little snapshots of what's going on.

Your brain is going to spend about a quarter of a second resting your eyes on the words and skipping forward. This is how your brain absorbs writing. Occasionally, it skips back, and you might think ‘Oh, I missed that, I didn't understand it. I got thrown off, I got confused. I need that bit of information again.’

Eye-tracking

Here's the second science-y bit. In an experiment, they put a camera on top of a screen and sit 230 people in front of the screen. Then, they track where their eyeballs looked. And your eyeball, when it's looking at a page of text on a website, is skipping about like a child on hot sand. So, what you actually get is people not reading. Beyond the first few options on Google, people just aren’t looking, for example.

We can use this information to shape the text, whether it's an e-mail or it's a presentation, or it's a document or a website. You can try and guide the reader to the bit that you think is important.

People only read 20 percent of your webpage

80 percent of the stuff on your webpages is stuff that people are not reading. In other words, according to research by Jakob Nielsen and others, people come to a website and on average they read 20 percent of each webpage. On average, they're giving you about a minute or two. Perhaps less.

If they like it or if it's information they actually want, however, they’ll stay. Jakob Nielsen, who is a guru of mine, describes website visitors like animals. They're hunting in packs trying to find the information they want. If they don't find it, they're moving on.

You have to understand people are not going to read all the stuff you give them. What is the logical inference from the fact that people are only going to read one in five words, or 20 percent of your website? Be more concise.

An experiment in readability

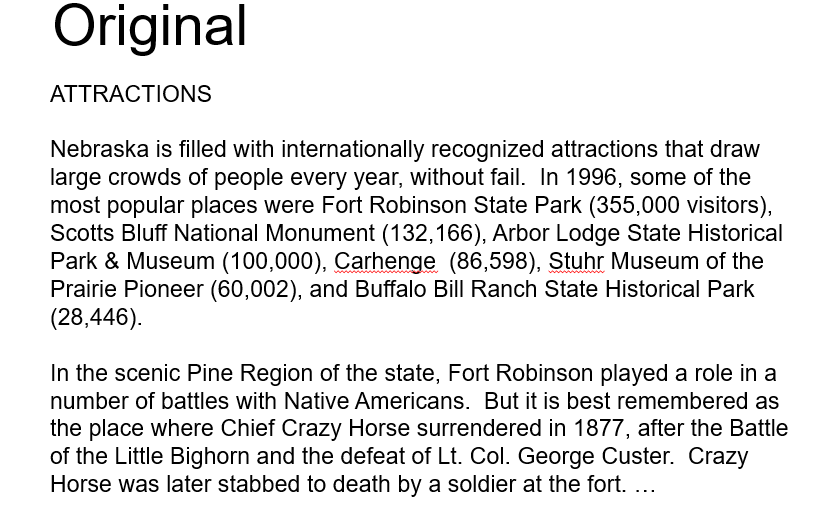

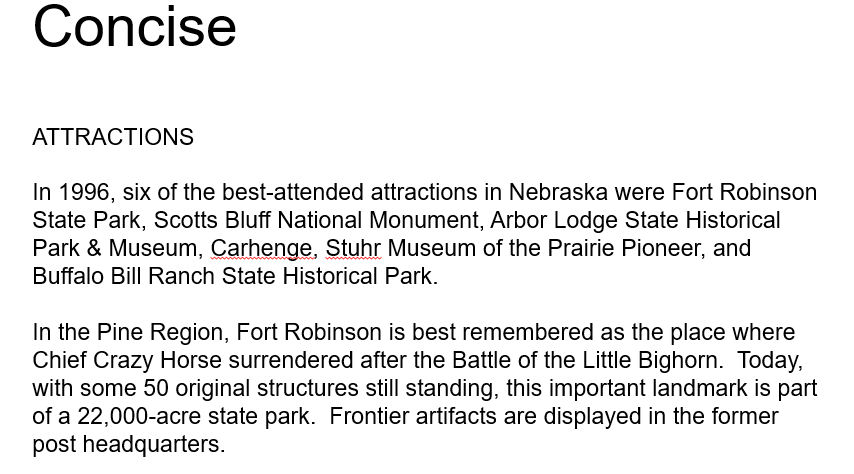

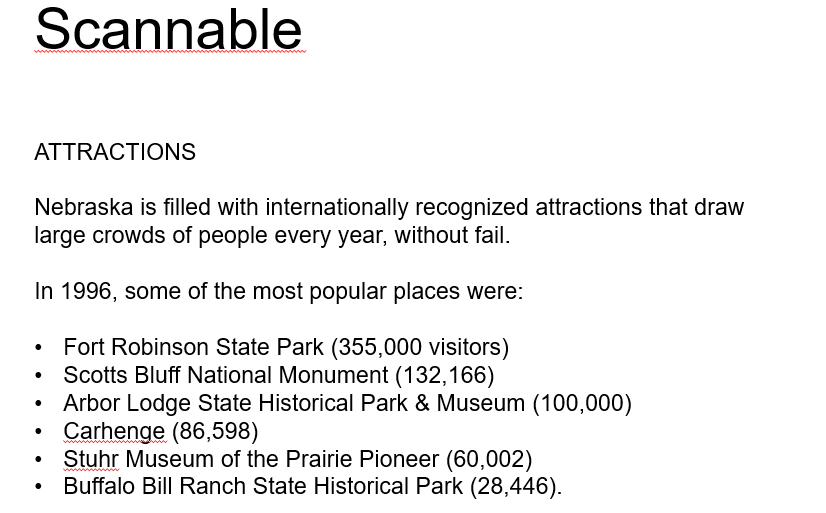

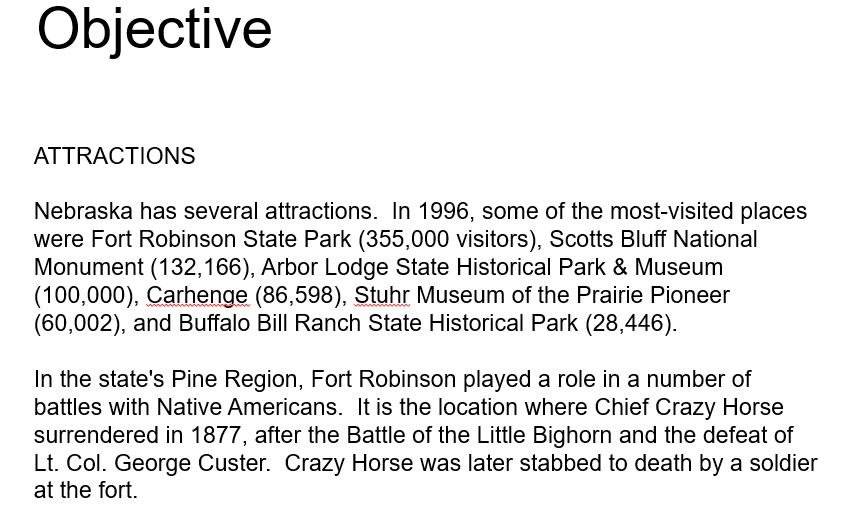

Jakob Nielsen did some research when he took some text, a piece about ‘Tourist Attractions in Nebraska’. The kind of information you need if you wanted to know the most exciting tourist attraction, which I think is ‘Carhenge’.

He took this bit of random text off the internet and he made some interventions into it with the objective of making it more readable, quicker to read, easier to remember, and what he calls ‘subjectively more satisfying.’ In other words, people thought that the text was interesting, good, readable, high quality and so on. If you were trying to write a webpage or an e-mail or a brochure or a CV or any kind of writing, you would like it to be like that too.

Here's what he did to achieve that.

- Firstly, he made it more concise. He wrote less stuff.

- Secondly, he made it scannable. With people's eyes moving all over the webpage, we'll meet with scannable text, such as short paragraphs, heading and bullet points. He gave the brain and the eye a clue about where to look.

- Third thing he did was making it more objective. This is Nebraska tourist office setting for sizzle, not the sausage. Now, I know we're always told in marketing that you’ve got to sell the sizzle and the sausage but actually, if you take it out, it makes it more compelling. People are cynical about marketing, so don’t give them anything to object to.

The combination of those three very simple interventions doubled the readability of that text. It's really simple. It’s not rocket science, you don't have to be Shakespeare to do that, it's just mechanical editing.

Shorter words are better

Okay. Next important tip, if I can give you one big thing to take away, it's this: substitute short words for long words.

I think Churchill said, ‘short words are best, but old words when short are best of all.’

That is a fundamental truth of writing. It's been proven by Daniel Oppenheimer when he was at Stanford University, who did a test where he took a piece of text and then he replaced all the words with longer synonyms of those words. Then he tested people's ability to read it, understand it, and asked them, ‘what do you think? Do you think that the author of this text is intelligent or not?’

Now, the instinct we have is if we use long words, we're important, we're clever, we're professional. Professional is the death word for writing.

Daniel Oppenheimer reckons that the opposite is in fact the truth, and he said in his report ‘Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilised Irrespective of Necessity.’

He concluded his report, ‘one thing is certain: write as simply and plainly as possible and you will be more likely to be thought of as intelligent.’ Wouldn't that be nice? Wouldn't you like to be thought of as intelligent? And that's how you do it. Use shorter words.

There is the science-y stuff. Now comes the copywriter secrets, or the tricks of the trade.

Getting people's attention

How do we get you to pay attention in this busy, complex, overloaded, information-rich world? Well, the first thing we do is we pick one thing to tell you about. One thing at a time.

For example, take an advert about a car that says: ‘At 60 miles an hour, the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock’. What this is honing in on is how elegant, quiet, sophisticated, well-engineered and luxurious the car is. But, they're just telling you this by saying how all you can hear is the clock. Apparently, in the factory, the engineers who built the cars were so upset about this, they said, ‘well we must do something about that clock, something's faulty with it.’

And, in the background of the advert there is the charming kids in their riding outfits. They’re on a nice country lane. You know, this is a lifestyle. But the messaging is sort of very subtle. And you do get a whole load of extra text telling you how luxurious it is, but the stand-out feature is one telling detail. If you can find the telling detail, that's the secret of good copyrighting.

The challenge we sometimes have with clients is on the homepage of a website or the first page of a document or the first paragraph of a document, they want to tell you everything. And the reality is you can't. If you try and squeeze everything in, you end up saying nothing. So, there you go, that's the message. One thing at a time.

Copywriters are story-tellers

The next thing we do is we tell stories. Human beings are wired for stories. This is what we are programmed to do. ‘Once upon a time there was ... and then ... and suddenly ... and so ... and they all lived happily ever after.’

This is a sort of a narrative that's built into our brains. We don't tell it always like that, but we might say, ‘your computer broke and then you went to the Apple Store and then you bought a Mac and then, and suddenly, and you know, whatever.’

You want to structure information so that we don't drop it all in on one go. The classic example is the inverted pyramid. At the top, in the headline, is the key information. It is the distilled summary. If you read nothing else, you get something from that. Then you get a slightly compact, more detailed version of the information. And then you get a much more detailed version of the information.

Journalists use this method all the time in newspaper articles. Now, when you read a newspaper, you'll go, ‘ahh, I see what they're doing.’

So, these are some of the tricks that we use to break through and hook you in. My old editor Matthew Rock said:

‘You've got to win the reader every page at a time. You've got to win them on the cover, you've got to win them on the table of contents, you've got to win them on every article; the headline; the stand first – you've got to get them to turn the page. It's a constant battle for people's attention.’

How do we persuade?

If you want to get people to buy something, take action, hire you, cast you... all of these things are important. I want to turn here to Robert Cialdini. He wrote a book called ‘Influence’, and Influence is sort of the bible of psychological manipulation.

It's very interesting to think about why we do things, and I think a lot of times we make shortcuts. You go into a supermarket, there are fifty different types of shampoo, so it's almost impossible to pick one. You go into a computer store and the guy is trying to sell you stuff and it's very difficult to work out what you want. So, how do you make decisions? What could we use to cut through all of that and figure out the right thing to do?

Some suggestions:

- Recommendations. Do what other people tell us.

- We like it.

- We substitute one bit of information for another. Does it look good? Therefore, it must be good. Beauty is truth and truth beauty and so forth.

Scarcity

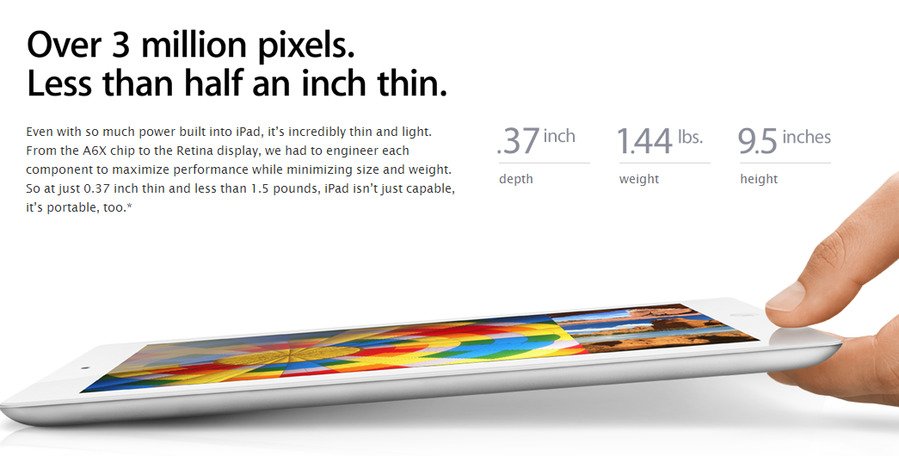

There are lots of tablets in the world, but there's only one iPad. It's a subtle one here, but if you are an art dealer, for example, what happens to the prices of art when the artist dies? They go up because they can't make anymore. They're not making any more land, therefore house prices, for some reason, seem to go up all the time. Scarcity is a way of getting you to do something against your better rational judgement, and if you can communicate scarcity, that's a powerful way of persuading people.

Social proof

It’s ‘doing what other people do.’ Loving it is easy. That's why so many people do. This is conveying to you the subtle message, ‘other people like the iPhone, therefore you should have one.’ The iPhone's a particularly sort of viral marketing. People get one because other people have got them like, ‘look, I've got an iPhone, it's fantastic.’

In this case, also, here's another example: J.D. Power. In giving consumer awards, they're telling people what to buy. And this is another example of social proof. This is the human instinct: safety in numbers, right? Ten thousand lemmings can't possibly be wrong.

Authority

So, if you've ever seen a famous footballer, pop star or politician endorse something, they are using their fame, their reputation and their authority to persuade you.

David Beckham, for example. There’s adverts where David Beckham is wearing a wristwatch designed for pilots. I'm pretty sure David Beckham is not a pilot. Why would I, as a pilot, buy a wristwatch David Beckham is recommending?

In this case, the authority they're relying on, actually, is their own. It's the A6 chip. They're bamboozling you with some technical information. A bit of voodoo stuff, right? BMW does this. It’s got some double overhead cam shaft, or something – they invent a name for some part of their engine – and they say it's got it, no one else has got it and it's very technical.

This is a kind of authority as well. And if you can find something in your business or find something in your track record or your CV or and put a name to it, or maybe get a bit of endorsement for it, then you give it authority. If you're an actor, if you've worked for a famous director, this is the kind of thing I'm talking about.

Commitment and consistency

Then there is this feeling of commitment and consistency. This is a very powerful psychological motivator.

I think what happens is we kind of make a decision about something. ‘I am now an Apple fanboy,’ for example. So, then people think they actually have to defend that decision. ‘I'm not going to climb down from it. I'm going to wear that with some pride and some satisfaction. I'm going to bore my friends about how Macs don't crash.’ Or I’ll say how elegant they are, but I won't mention the fact they cost three times as much as other devices.

So, you've gone through a one-way door, you've put your finger in a finger trap and you don't want to admit you've made a mistake, and in fact you are committed to it. I think also, Apple does this very subtly in other ways. Like, they have the Genius bar. Now, if any other company suggested a Genius bar, the response would be ‘oh we mustn't do that because we don't want to appear arrogant’. But Apple know that if they have that, what they're implying to Apple buyers is: you're kind of a genius too.

Likeability

Steve Jobs’ great insight into marketing is: ‘If you don't have somebody hate you, nobody is going to love you.’

People like buying from people they like. Likability is another motivator. If you could be likeable, if you can establish that, you can also win converts.

Reciprocity

If I give you something, you feel obligated to give me something back.

You can download this if you've got a Mac, PC, it doesn't matter. It's free. Of course, you're going buy some tunes and stuff, and you're much happier to use iTunes now you've got it than some other Windows Media Player or something like that, or some open source thing. But it's reciprocity, it's something for nothing, so you feel obligated to reciprocate.

And, they're very good at overcoming objections. What happens if my computer goes wrong, I want some human being to talk to. So, they put human beings on their website.

Yet when you try calling Apple with a problem, they'll send you to the Apple Store where you have to make an appointment and you pay 300 pounds to have your broken iPhone replaced. Apple has, in my opinion – I might be wrong – pretty much the worst warranty deal going for a computer and yet the perception is you get better support. Interesting.

Writing tips and tricks

So, now we come to the, sort of, tricky stuff. Here's a little tip: try and use the most common words in the English language. Not just your words, but actually what Alan Sugar, I'm almost embarrassed to quote him, but it's a lovely phrase, calls ‘Export English.’ The simplest language you can use.

Take the tool Up-goer for example. You type in any piece of text and it checks it against a thousand-word vocabulary that has the most used words in the English language. It's very hard to write something that's going pass this test, but it's a useful tool.

Ask questions

Ask the reader questions. Think about the information that you know that the reader would like to know. Research out the stories. I find doing interviews even for something I know quite well, ringing somebody up and having them explain it to me in their terms is a really good way of understanding it.

I often find with clients that they say to me, ‘I can do your job. It must be very difficult being a writer. I'm rubbish at that. Blah blah blah.’ I go, ‘that's fine ‘cause I'm here to help. Tell me about your product. Tell me what you do or tell me about the company.’

Then they proceed over 20-30 minutes on the phone to give me an incredibly eloquent, succinct, detailed, thoughtful exposition of whatever it is they're talking about. It's almost like they feel like they can't write but they can talk.

Asking questions and answering questions. This is a secret to good writing.

Replace long words

Here's a much simpler tip. Replace the long word with the short word.

Contracts are particularly bad at this, but actually it's very easy for websites and letters and things to kind of get all flowery and formal. Cause you feel like oh, ‘I want to be professional. I want to be taken seriously. I want people to agree with me.’ But shorter is better.

It was written in the passive [by zombies]

Right. The passive. I'm not going to explain it, but this is how you recognise it. There is no subject. There is nobody doing the doing, okay? So, if you can add the words ‘by zombies’ to the end of a sentence, it is very likely to be a passive sentence.

So, that's a reply to the zombie test. The mat was sat on by zombies. Passive. Mistakes were made by zombies. Passive. The book was stolen by zombies. You get the picture.

There are some cases where the passive is ok if you do it by choice, deliberately. If you're conscious of it and you understand how you're using it, then maybe you want to emphasise something in a different way. So, you put that thing first and then you turn the sentence around. But generally, you want to get rid of the passive voice in your writing, because the brain comes along, dum de dum de dum de dum, ‘oh I can't find a subject.’ And the brain starts looking for that and then your eyes skip back and then you lose interest in what you're reading. And then you turn the page, you flip the article, you go back to the next webpage. Bang, you've lost the reader. Why? You used the passive voice. So, passive detection kit. By zombies.

Have a conversation

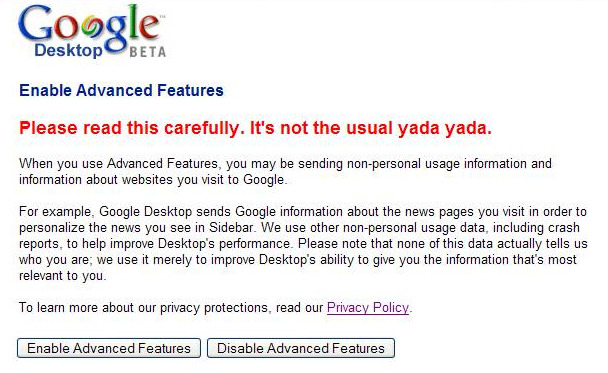

This is the biggest tip for the evening. Here is another bit of text – why do I like this text?

It sort of flips the conventional on its head. It's not the usual yada yada. So therefore, what you expect this to be, which is the usual, is not. It doesn't look like a click through licence, does it? No. Like 20 pages of legal text written by some lawyer somewhere. I will read as many click through licences as you will pay me to. The reality is though, we don't.

However, this is giving you information that's actually useful to you. It's giving you choices that are actually pretty clear. And it's telling you in everyday language. Yeah, there's a bit of legal stuff there if you want to find out more, but it's talking directly to the reader. Us, you, we – it's a conversational approach.

When we're at school and particularly when we're at university and especially when we get into advanced degrees, we think ‘oh, I can't use the first person.’ First person is I or we. ‘I can't say I. I can't say we.’ And often in companies we're kind of really nervous about say ‘I’ or using the company name. It's all got to be very sort of hesitant. You know ‘people may think, oh perhaps companies prefer to do this.’ No. It's fine. Talk to people. We, you, us. It's fine. I give you my permission.

Instruct the masses

I also give you permission to give instructions. Tell people what you want them to do. This is absolutely fine. And especially now when you're trying to get people to take action. You're trying to get people to read through and do something. You're trying to get them to sign up as a reseller or a partner. You're trying to get them to buy your products. Sign up on your social network, whatever it is.

Say in order to take advantage of this offer, ‘Go online today.’ Give people instructions. It's also a way of avoiding using a company name, using a subject, saying you or us or we if you feel embarrassed about it. So, give instructions.

Shoulda, woulda, coulda

Here's another classic copywriters’ trick. Avoiding defensive language. This means being really nervous about being categorical. So, people use things like would, could, might, may, we don't want to be specific, so up to, around, more than. But people react to facts. People react well to specificity.

This is what Steven Colbert calls ‘truthiness.’ It's like the truth but sort of not quite. There's truthiness in data. There's truthiness in numbers. When I was at university my history tutor said, ‘Matthew, you know it would be such a good idea if you would put a few dates in your essays.’ Truthiness.

Easy on the punctuation

This is something that at Articulate we care very passionately about. Having thought about it quite a lot and argued back and forth when we were writing our style guide. We don't like punctuation. We don't like anything that gets in the way of that smooth progressive transfer of our information into your brain. So, we object to ampersands. We object to percent signs. We like words.

We don't like capitalisation. It's a common thing actually in technology companies, maybe others too, to capitalise a noun because it might be a product. It might be a trademark. But, actually put it in lower case. Also, for headlines, subheadings, capitalise the first letter, make the rest of it look like a sentence. Why? It's easier to read. You're less likely to have one of those cascades, one of those drop out moments.

Spelling out numbers is another one. I think, I might be wrong about this, I think we now have decided to also write the word ten. One-ten. 11-20. This is a big revolution with much philosophical and existential angst. Yes, we now say ten. AGFA, another gratuitous four-letter acronym, right? People stumble over these. If it's DVD we do all know what a DVD is, right? But if it's CMS? It’s less clear. ‘Content management system’, if you're wondering.

So, you need to use the right acronyms for the right audience and if they're not sure, spell it out or describe it. I particularly hate trademark bugs. I would like to abolish them because they're speed bumps. But you have to use them. So, we are punctuation minimalists at Articulate. We’re just like, ‘Ah! Punctuation, let's get rid of it.’

Use a style guide

Here is a four-word style guide template:

- Audience

- Viewpoint

- Language

- Structure

It’s very important to have a style guide to think through how you want to communicate with people. How you want to use language. How you want to be different from other people. This is my little template.

- Who are you writing for? This is very helpful to understand this.

- What education level do they have?

- What else do they read that you could copy, that you could emulate, that you could relate to?

You could take it to your boss and go, our audience all read Computing magazine or they all read The Times. So, we want to write like that, we don't want to write corporate BS. We want to write stuff people trust and believe.

Viewpoint, language and style

Here's an example of a viewpoint. Write from the viewpoint of a trusted advisor. Write from the viewpoint of a personal friend. Write from the viewpoint of a techie genius. Think about where you're coming from and what that means for the language you use. If you choose the right viewpoint, you're going to change the way you write.

What language is appropriate? Here's an example: use good business English. Use the language of school children. Use the words of nursery rhymes. Use techie language. Pick the right sort of language and structure. This isn't so much about inverted pyramids and story spines and things like that. I have an example of structure that might be like ‘create a conversation with a reader.’ It might be ‘bombard them with as much information as they can absorb in two and a half hours.’ But think about how you want to engage them.

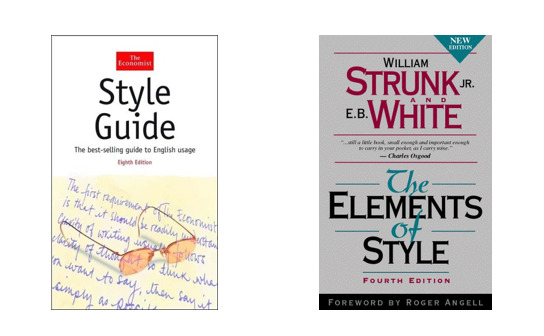

At the very least, think about writing, think about style. These are two very good books:

There is some slightly iffy bits in here you might become aware of, but it's still very readable and it's thoughtful. You can actually sit down and read this one, ‘Strunk and White’, in half an hour to an hour on the train. And it's very cheap, fun to read and interesting. You will be a better writer if you read that.

How to write headlines

How do we write headlines? When I say headlines, I mean – well, ‘cause I'm an ex-journalist, I'm sort of recovering. ‘Hi, my name is Matthew. I'm a recovering ex-journalist.’ I mean headlines in a magazine sense. But, depending on what context you're coming from, you can hear tweet. You can hear Facebook post. You can hear email subject line. It's the same thing. It's the invitation to the party. It's the bit that they read before they read the rest of what they're going to read. So, headlines are all of that thing. It's that top stuff.

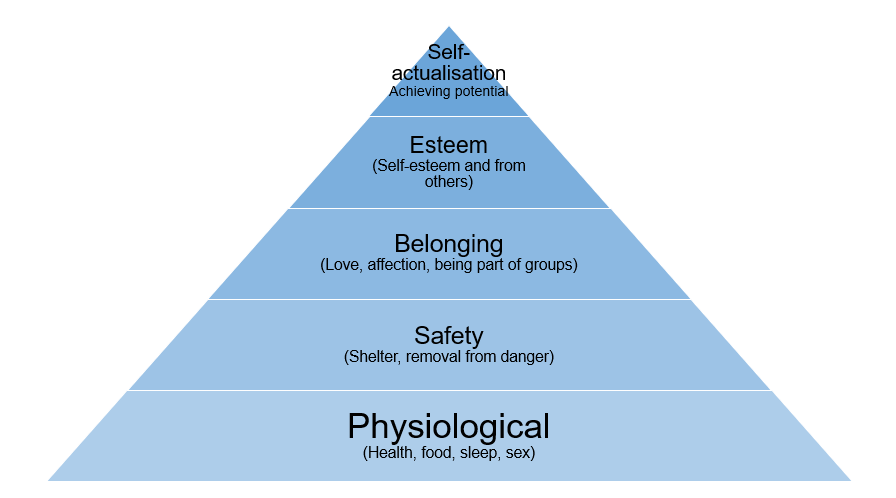

Here’s Mazlov's hierarchy of needs:

Theory is, you need these things, food, shelter, sex and so on to exist. That's sort of fundamental; if you don't have that, you'll go extinct. And then you move all the way up to self-actualisation, which is sort of a luxury need. You can't have self-actualization if you're starving to death.

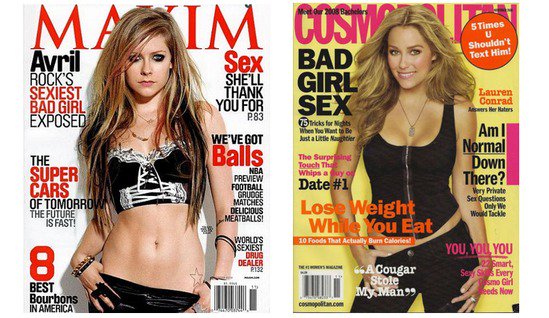

So, this is stuff that motivates people. This is stuff that drives us. Why should they read your headline? Why should they read what you're going to say? Why should they read your copy? Well, let's have a look at some examples.

Yes, losing weight really isn't about food, but it's about nutrition, sure... So, there's a lot of sex there for sure. I think there's a certain amount of, how can I put it? Belonging. This idea of being part of a group. There's certainly some fashion, there's some trends. And there's quite a lot of self-actualisation going on.

So, these are psychologically appearing to those basic instincts. And you're headlines, subject emails, subjects, whatever, can do the same thing. Here's a little bit more upmarket:

More grownup stuff. Same thing, though. Sex, belonging, food, self-actualisation. Same stuff.

Headlining secret

Here is the secret of writing a great headline. Write 50 of them and pick the best one. Ouch. I have to admit in nearly 14 years of professional paid writing I've never taken this advice. But I am confident that it would work. I probably have written maybe a dozen attempts at something and sometimes when clients go, ‘We don't like the title, can you come up with another one?’ I've probably sat there and gone, ‘try this one, try this one, try this one.’

Donald Murray wrote this book 'Writing to Deadlines', which by the way, of all the books I'm recommending, this I think is the best and most entertaining. It’s the most interesting and insightful. If you're interested in how journalism works, this book will tell you. And he's no slouch as a writer. He's got a Pulitzer Prize, so it's a well-written book in its own right.

But this is his recommendation: write 50 leads and 50 headlines.

Now his idea, his sense is if you do that, the rest of the story will present itself, because you've got it all straight in your head by the time you've got to the end of that list. You know you'll have come at the story from so many different ways, you'll know what you want to say.

Articulate’s headline tips

Here are some tips for writing better headlines:

Alliteration

Yeah, using the same letter at the beginning. 'A display that's not just smaller. It's smarter.' is an Apple headline. S and S. It's not just smaller, it's smarter. It just emphasises the point you want to make. These are rhetorical tricks.

Rhyme

- 'iPad isn't just capable, it's portable, too.'

- 'The world's largest - and smartest - collection of apps.'

Well Apple aren't rhyming. It's not a nursery rhyme, but they're using end rhymes here. Est, est; able, able. And that again, gives a little bit more emphasis on the words you want to use.

Repetition

'It's breakthrough technology. For a breakthrough display.'

Now you know, it's quite hard, I get picked up by proof-readers for repeating things. I think I'm doing it very cleverly and with intention, but it just looks like lazy writing. But here is an example from Apple webpage using the same word breakthrough. Obviously, what they want you to think it's new. It's a breakthrough.

Using an analogy

'iPhone 5 is made with a level of precision you'd expect from a finely crafted watch, not a smartphone.'

This is another way of getting through the noise. Don't just describe it. Get it into their brain with something that's tangible. ‘Finely crafted watch’ does this.

Contrast

This is a sort of ironic twisting of things. So here they are contrasting the big picture with the details:

'We focused on the big picture, but never lost sight of the details.'

Here they are contrasting three million with half an inch:

Apple just sort of write. I don't know how they do it, they must have a team of really well-trained monkeys somewhere just bashing this stuff out. Did you know that if you put an infinite number of monkeys into a room with an infinite number of typewriters, eventually they will write, ‘hey, hey, we're the monkeys’?

Write bold statements

Be a bit aggressive. Remember Steve Jobs, ‘nobody is really loved unless somebody hates you.’

Just take a risk with a headline. Say something outrageous. Say something unexpected. Say something with intent, and really make your point.

I like Buy it like Buffet very, very much. What I really think is interesting is where the headline started. It's a real sort of factual rather TV-esque thing. And they've sort of sexed it up and made it really compelling.

News hook

Tell them something they didn't know. Use something information. Use a data point. Put a date in your essay.

And the test for a headline is when you've written it, is this a headline I would click on? Is this a headline I would happily tweet? Is it worth commenting? Does it provoke? Does it get a reaction? Does it say something interesting? And when I say headline, email subject, tweet, Facebook, subheading, whatever.

The copywriter’s working process

So, how do copywriters work? We are in our darkened rooms with our bottles of whiskey and a cold flannel on our head, trying to meet our deadlines and get the words out. But actually, there are some tricks and techniques and things that we do as copywriters at Articulate that I guess might help. And I'm going offer them up to you now.

The first one, write every day

Write something every day. Ideally, write 500 words as a minimum. Get into it. Do something. Even if it's not very good. Even if you're not happy with it. Even if it's not for publication. Just developing that fluency, that sort of feeling of comfort with words, is key. That feeling of not censoring yourself is a really, really powerful way of unlocking your inner copywriter.

We've got this little calendar here ticking off every day I've written something. If you were to write 1000 words a day, you could write a really substantial novel in a year. A novella, short novel is 60,000 words. Write 1,000 words a day and you keep at it religiously, you could write six of them. Somebody check my math. Six of them. Six, you wrote six novels a year. I mean okay, you also have to do editing and find a publisher and have a job and all that stuff. But. It's astonishing how much you can do if you just stick at it.

I like to use the analogy of a river and a rock. A rock is really, really strong and hard and difficult to break. But over time with persistence, the river will win. A little bit every day is like the river.

Learn to touch-type

Learning to touch type is the single most powerful productivity tool you can have. You're sitting at your computer all day, writing emails, writing websites, doing stuff. If you can get fluency from your brain onto the screen, onto the page, without having to sort of stop and wait for your hands to catch up or wait for correcting mistakes, it's going to speed you up. So, learn to touch type.

The image above shows an app called ‘Type Fu’. It’s really easy to use. Access it in Chrome or download it on your Mac. It's free and all it asks for you is a bit of time and a bit of commitment and a bit of practise. And even a little bit of time practising touch typing is going to make you faster. I don't think there was a good writer who was not also a fluent typist. At least until we invented the typewriter.

Say no to meetings

This is the biggest obstacle to producing copy. I'm going to get shot at if I get this wrong, but I think it is true to say that at Articulate we have one meeting a week amongst ourselves. It's a long meeting, but just one. And I have another one for my other business Turbine. There, I have to talk to the developers and sort of figure out what the hell they're doing and what we should do next.

So, I have two main meetings a week. Yes, we talk to clients. Yes, we have meetings and phone calls and conference calls and interviews, but actually internally we're trying to not have endless meetings. And I think meetings just disrupt your day, they get in the way, you have to go and sit in a room, you have eight people in the room and there's always one of them that's going to talk about some distracting thing that's not relevant and everyone else has to sit and listen. I honestly, I do not know how some businesses actually get anything done. When I go in and see them, and I see people's diaries and they're at meetings every hour, going from one room to the next room. All day they're in meetings. I don't know.

Don't show up. That's my recommendation. Just don't go. See if the world ends.

My theory is, actually, it'll take a certain amount of time and then people will start noticing you're not going to all these meetings and that could be risky. It could be risky. But if you can make that time long enough for you to get some capacity to do some real work, get some actual stuff done, maybe do some writing, by the time they notice, you're already way ahead of everybody else.

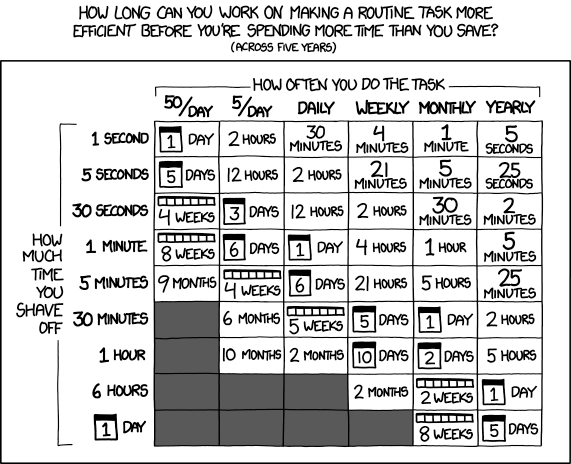

So, that's my theory about meetings. Don't turn up. And here I absolutely adore this diagram. This is a table that shows you how much time you will save over five months, by small improvements in changes in the way you work:

Look, just five seconds a day, five times a day. If you do something repetitively and every time you do it, you can change the way you do it, you save five seconds, you do that five times a day, over five years, that adds up to 12 hours. Twelve hours! You could go to the park. It's a lot of time, but what if you're going to a meeting every day for two hours that you don't have to do. In five years, that's two months. Two months of precious time. You could learn another language. You could learn a musical instrument. You could have a really long holiday. Two months is an incredible amount of time. And all you have to do is not show up for a meeting every day.

And if you just look at everything you do – maybe you need to get a clipboard and a stopwatch – and just say, ‘What am I doing today? What can I cut out? How can I save some time?’

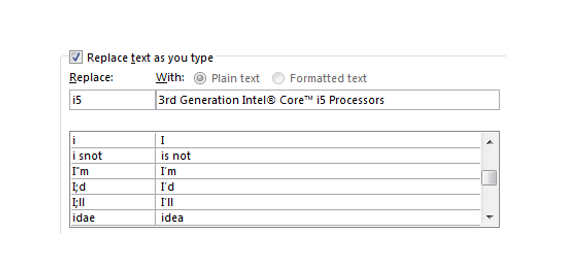

Here is a tip. Here is a little thing that can save you that five seconds. This is Microsoft auto text:

Years ago, I was doing some work for a client for HP. And it was being co-funded by Intel and we had to mention Intel processors a lot. And when we mentioned an Intel processor, we couldn't just write I5. Core I5. No, we had to write, third generation or second-generation Intel Core I5 processor with capital letters and trademarks. This is a lot of words.

I mean, I don't mind because I get paid by the word. But you've got to type all that. Well with this little thing you type I5 and it auto-expands like on your smartphone. Great, I5, I7, I3. So, you know, maybe there are frequent phrases that you could put into this and it would automatically remember them, saving you typing them. I learned this on Monday. I didn't even know this existed before. So, I'm sharing some new information I've discovered in the field and I'm bringing it to you.

Multitasking

Matthew's recommendation: don't do it. Because actually it makes you stupid and it makes things hard to remember and it's very hard to concentrate if you're trying to do your email and you're trying to write an article and you're listening to some music and you're doing this, that and the next thing It fries the brain.

Now, there's an experiment done at UCLA where they had students doing card sorting exercise. So, a contest of concentration and attention. One group did it in silence, one group did it with some random noise. Fine. They both did equally well. They both got the job done, but afterwards the people who had the random noise couldn't remember what they were looking at. And the people who did, who had silence, could remember what was on the cards. So, multitasking, just even with music, even with a bit of noise is just taking away a little bit of your brain.

And noise increases stress hormones. Cortisol, adrenaline. I don't know about you, but I could do with a bit more chilling out. A little bit less adrenaline. I could do with cutting out some multitasking. Which brings me to silence. Silence is an incredibly powerful writing tool.

What I want you to do is just listen, tune into the different noises you can here, and the feelings of maybe the air on your face and the thoughts bubbling up in your brain and just pay attention to what's really going on, beginning now…

Isn't there a lot happening? There's so much more in your capacity if you have some attention to give to it. And silence is not the absence of noise, it's the presence of mind.

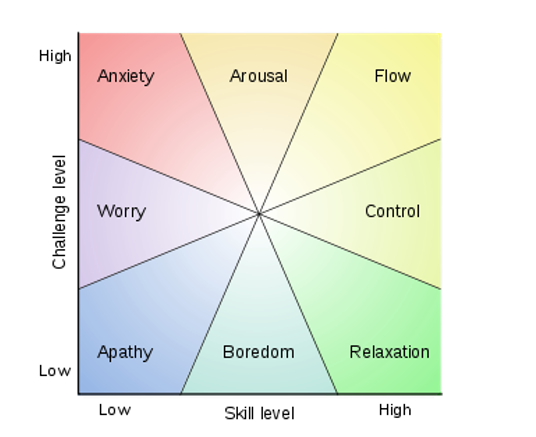

What else do you need to do a good job as a writer? You need concentration. You need flow. I'm now going to read you the name of this guy who is very hard to pronounce and I looked it up and I might get this wrong. He is called Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He is a Czech. Anyway, if you Google ‘flow’. Flow psychology, you will see his name.

And his theory, his understanding is that when you are doing something that requires a high skill level and a high level of change or high level of attention, you can enter into a flow state.

If you've played sports and you’re in the game, you've scored and you're in the zone. You're playing a video game and you're really kicking ass. You're writing, and you've got the whole article in your head. You're writing a computer programme and you know exactly how that program's going to run without even compiling it. This is the state of flow. Do you recognise this? Have you experienced flow? Do you experience it a lot?

This is the most productive state that we can be and when we're trying to write or trying to concentrate, and every time there's a phone call, every time your instant messaging pings, every time your phone goes bzzz and something's happening, this interrupts that flow state. It takes you out of that moment and puts your mind and your attention somewhere else.

What does that suggest you need to do in order to concentrate and have flow? Remove distractions, put the phone on ‘do not disturb’ close your email client, put your phone on mute or in another room, shut the door.

There was some research done and it's a beautiful book called Peopleware. It's a classic about people in companies who are very interested in productivity, especially programming companies and software companies. I was a software entrepreneur. I was very interested in productivity and I read this book and they said, ‘you've got to give everybody a two-person office’ and I thought ‘I'm not doing that, I can't afford it’.

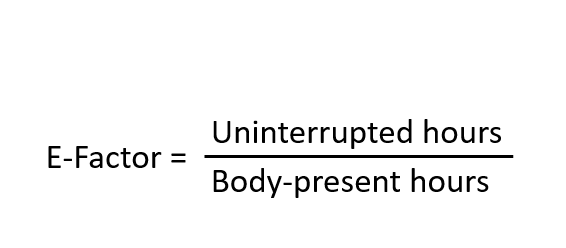

But, when you start looking into the productivity benefits of allowing people to shut out distractions, the payoff is gigantic. This is the E-Factor:

This is their way of measuring how for productive people could be and how conducive your working environment is to flow.

‘Uninterrupted hours’ means the time you can spend working without having to go to a meeting, without the phone ringing, without the email pinging, without you being distracted from the thing that you want to do versus the number of hours you actually spend in the office. And they found that they measured in different organisations, different companies, ratios of point one, which is kind of horrible. That means for every 10 hours that an employee is sat in the office, they're doing one hour of productive work. Imagine you writing a salary check every month and you're thinking, well, 90 percent of that is wasted. That's crazy. The best they measured was 0.38, so maybe four hours out of 10 was productive work the other six hours, distracted.

So, in an environment like that, actually it really makes sense for people to go to meetings. How else can you shut out all the crap? It's kind of really weird. Meetings are an immune response to a corrosive, broken productivity environment. But if you fix the environment, you don't have to go to the meetings and everyone can get their job done.

The joy of notebooks

This is a small thing, right? Every writer should have a notebook with them at all times. Why? Why should you have a notebook with you?

You don't know when inspiration is going to strike. You don't know when you're going to have that lovely turn of phrase. You don't know when you're going to come up with the answer to something. While you’re taking a break maybe. Taking breaks is actually part of a productivity regime because if you walk away from what you're doing, your brain has a chance to digest and synthesise. Quite often, you wake up in the morning, you've got the answer to the problem you had the night before. You sat up all night, you would have think of it.

I will show you a couple of little notebook hacks. Here's the Moleskine notebook hacks:

- Get a little rubber band with a pen on it. There you go. Now you've got a pen with you the whole time.

- Little sticky index cards so you know where to start your next sort of writing.

- And this one's my favourite, write the date or dates, start and end date of the Moleskine, of the notebook on the side and instead of storing the spine out on your shelf store them paper out, and then you can see which notebook you're looking for if you have to go check something. I love that.

Find your motivation

Copywriters are very good at self-motivating. Find out what motivates you and apply it to yourself. For me, it's biscuits.

There's a lovely website where you can sign up and say, if I don't lose this much weight by this date, or if I don't finish my first draught of my novel by this date, I'm going to donate $200 to the Republican Party. Or pick your anti-charity of choice, or I'm going to donate $500 to the Ku Klux Klan or some crazy awful thing that you don't want to do. And you pay the money in and then you get somebody to validate whether you've done it or not. And if you haven't done it, the money's going to those awful people, right? This is very motivating. Guilt and fear, very motivating. Cookies, very motivating. Deadlines, very motivating, right?

Deadlines

One of the things that writers have to deal with is this constant endless deadline, deadline, deadline, deadline, deadline, deadline. It's almost like being back at school. And after a while they sort of stop feeling that fear. It just becomes a normal part of life. Like, I don't know, going to the gym or getting up in the morning or something.

I do like Douglas Adams’ little joke. He said, ‘I love deadlines. I love the sound they make as they whoosh past.’ But actually, they can be very powerful and very effective if you set yourself a deadline, if you make a commitment to a writing buddy or something like that. That is very, very powerful.

The unexamined life

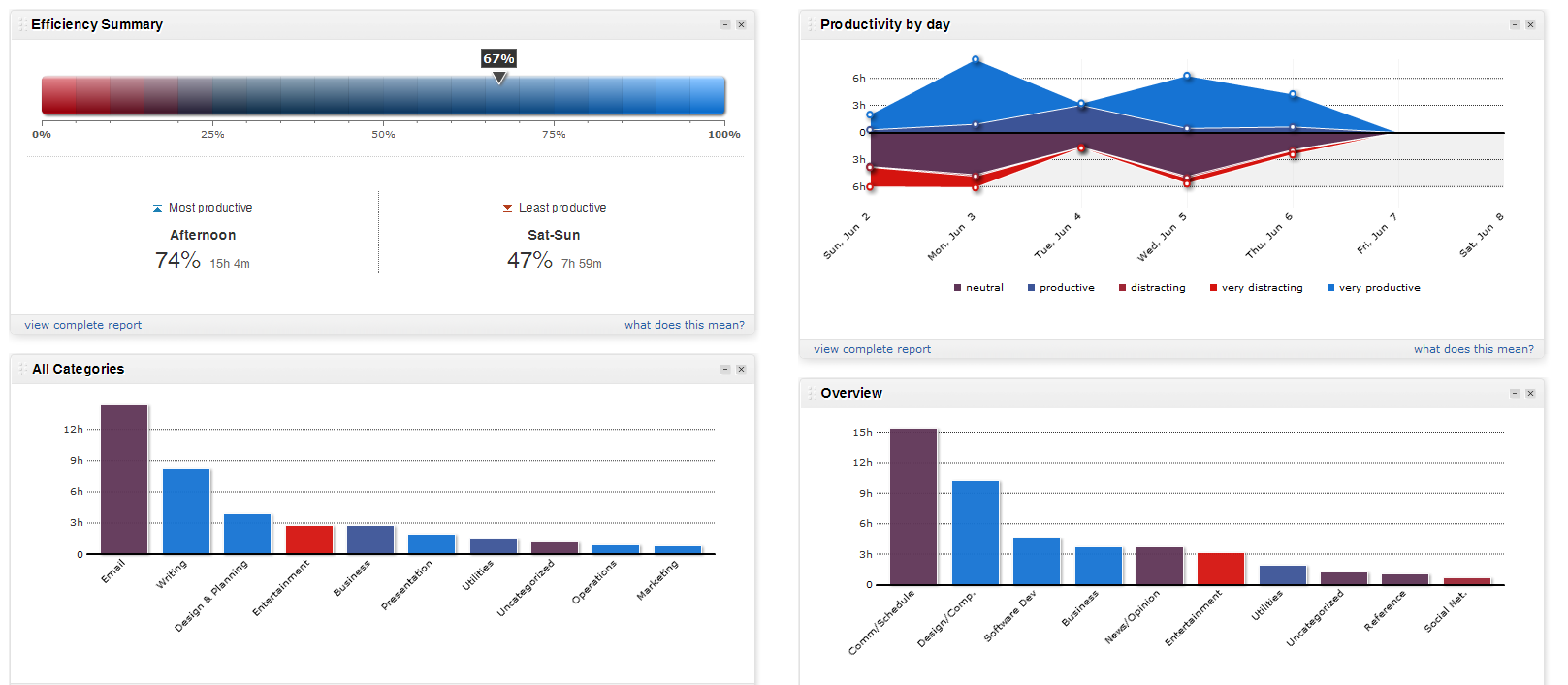

The unexamined life is not worth leading according to some old Greek guy. This is a thing I'm looking at the moment called the Rescue Time and it's like a tachometer on your computer:

It tracks everything you do, every webpage you look at every application you'll open, and it then produces these sorts of rather nerdy graphs about how much time you spent doing email, how much time you spent doing planning and how much time was productive versus not. So, the blue is productive time and the red is unproductive time.

And then it starts giving you information like, ‘you're very productive in the afternoon and you're not productive on the weekend at all.’ Well, okay. But over time it's giving you more and more information and that is useful feedback. You can also hit a button in it and you can say, ‘I want to concentrate’ and it locks you out from the applications and the websites that it knows distract you. That's quite useful.

Tools to find the time

There is a website called Write or Die. No, it doesn't come and kill you. Don't worry, it's not that scary. But what it does do is you're typing in your text into Write or Die, and if you've set it onto uber draconian mode, if you don't keep writing, it starts randomly deleting bits of text. So, you're there for half an hour and you're not stopping writing, you're just going to keep going at it.

And there are distraction-free editors. There are lots of tricks and techniques. What I'm trying to impart to you is this idea that, look at what you do and think about it, measure it, analyse it for a bit, and maybe there's a better way. Maybe there's a new more efficient way. This is the copywriter approach.

Here's a trick that I learned this week: Top of the hour. So, every time it gets to 12:00, 1:00, 2:00, you spend 15 minutes concentrating on the most important task for that day. The rest of the hour can go to the usual things. Your friend calls, meetings, emails, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. Just 15 minutes, at first. But probably what's going to happen is you'll get so into it you'll spend the rest of the hour doing it. It's a trick to hook you into that flow time.

The other version of that, is the Pomodoro. On the first day you set Pomodoro to 55 minutes, then take a five-minute break. Then you do another 55, five-minute break, another 55 minutes then you take 15 minutes break. Why is that effective? For some reason, you know it's going to end. Well, you know it's finite time. For some reason it makes you just keep going, keep going, going. And then you find you’re eager to start again. You’ll find yourself saying, ‘oh, no. Let me go for another let's say five minutes.’ It's very weird but it's really effective and it keeps you moving.

What is writing, anyway?

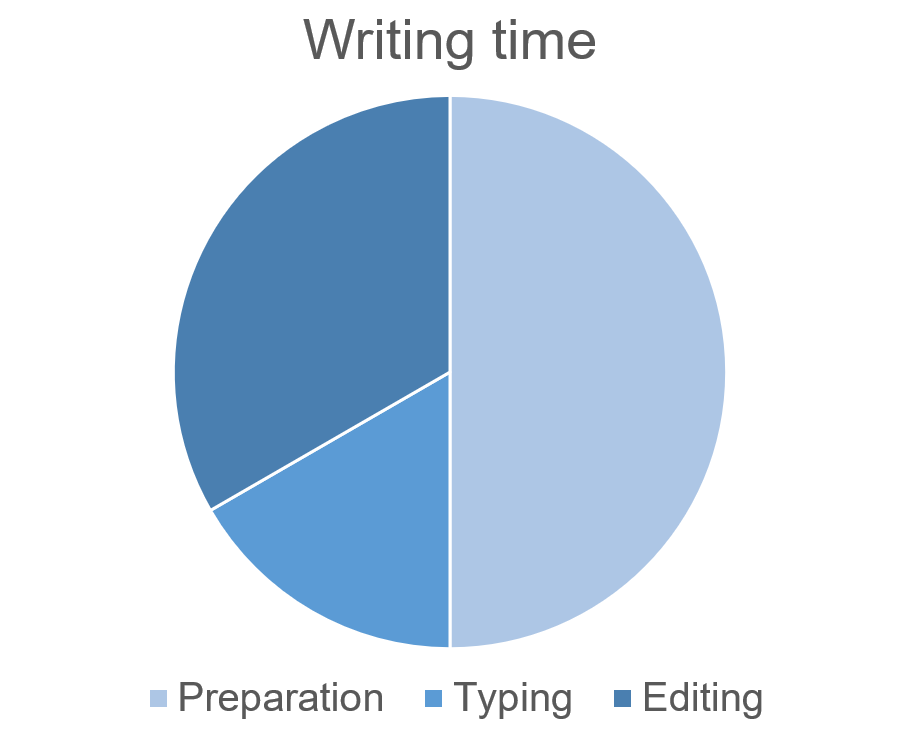

Here is a theory of breaking down writing:

Now most people think when they're writing, it's start up a computer and write. Writing, that's what you do. Actually, the majority of writing time is spent doing something else. At least for me. At least half of it typically is spent doing phone interviews; thinking about it; doing mind maps; sketching things out; doing some research; looking at the Internet; probably playing a game and getting a bit distracted. But it's not actually typing.

Only about a sixth of my time is actually spent typing because if you can touch type, you can write plenty of words in an hour, no problem. So, the actual writing doesn't take very much time. If you know what you want to say, you can just get this copy out. And then a third of my time is spent editing. At Articulate, we do peer editing. I write something, someone else will look at it; someone else writes something, I'll look at it. It works very well to do that. So, there's how a lot of time that is spent. If you can divide up the work, actually the process of writing becomes much more efficient.

Research

Another thing we do, we look shit up. If we don't know something, we go to Google and we figure it out. We don't guess, and we don't pretend. If we don't know, we don't ignore it. We don't know how to spell something; we don't know the product name; we don't know the date of something – we take the time to look it up. Google, best thing that happened to writers.

Mind Maps – that’s another thing that will help. Use them.

The power of two letters

TK.

These two letters are the most powerful tool that is in the world of copywriting. It means ‘to come’, as in to come later’ or ‘I'm going to fill this in later’. It's a combination of letters that does not occur very often in the English language. There's that American rap group called Outkasts that's spelt with a K, and only one or two other examples there. In some contexts, Telephone Kiosk is another example. Generally, it's not common.

So, if you just type capital TK and carry on writing, it saves you having to stop and interrupt your flow, interrupt you're typing, and you can say, ‘Neil Armstrong landed on the moon on TK July in 1969.’ Just put TK 1969, and carry on writing. I haven't stopped, and I've come back afterwards in the editing stage and I'll fill that in.

Or if I'm really feeling lazy, ‘TK amazing introductory sentence’, then put it onto the next day. Because that's not hard to do. If you just get on with it, by the time you've written the rest of it, that first sentence is going to come easier. You can do that now. So, it's a way of just skipping past writer's block and then you just do Ctrl F search for TK and replace.

The power of the SFD

Shitty First Draft or SFD. The shitty first draft is a writer's friend. It is the antidote to writer's block. It's like, ‘I don't care how bad it is I'm just going to write it because I can fix it in editing’. Like when you’re adding in video effects, and I don’t have to worry because ‘they can make me look fantastic in post-production by adding hair and the illusion of three dimensions.’ And Ernest Hemingway said that the first draught of anything is shit, so I have authority on my side that.

Spelling and grammar in a first draft

My recommendation for Word is I wouldn't use the squiggly lines, but instead I’d click on the button that says, ‘spelling and grammar check’ and actually consciously do a grammar check and a spell check.

Also, use Microsoft word and go to the options page and tick every box for it to check, because there's a bunch of stuff in there that you can have it checked. Most people don't use it. Switch all of that on. You don't have to do what it tells you, but it's useful to be told. For example, Microsoft Word wants to capitalise the word Trojan because people who come from Troy, they're Trojans. Well, we don't often write about the Trojan war. The other Trojan is an American brand of condom, which we also do not write very often about. Otherwise, in the context of an antivirus it's a small T. So just because Word wants to capitalise ‘trojan’, you don't have to.

Proofreading

Use proofreading, right? This is an advert in an American newspaper:

Tens of thousands of dollars. I would say that is a career limiting typo. Not Texas, but taxes. If you don’t have someone who can help you, try a site like wordy.com. You pay them a modest amount of money, you upload your Word document, they proofread it for you and you get an answer back within a couple of hours. Fantastic. Proofreading is good.

Readability statistics

Use readability statistics.

I'm not going to get into all the maths of this because of time. You can just go look it up on Wikipedia, but readability statistics is a very useful bit of mathematical feedback on how easy it is to read your copy, which is kind of interesting to know.

The four permissions

We are very near the conclusion. So, I am going to give you permission to become a better writer. In fact, you are already a brilliant writer. I give you my permission to write. Just do it.

I give you my permission to be yourself. Find your own voice, find your Purple Cow.

Sethgodin.com is his website and you can read ‘Purple Cow’ by Seth Godin to find little encouraging words there as well. Why would you read it? The idea of a Purple Cow is something remarkable, something unique, something different. And we all have a purple cow and we all have something that we can say, some unique selling proposition, something exciting. The trick is to find it and to rehearse it and to keep saying it and to keep expanding it. And by some incredible magic property of purple cowness, the more you explore your purple cow, the more purple it becomes.

I give you permission to experiment and have fun. This is Dr. Horrible, a.k.a. Neil Patrick Harris:

It’s from Dr Horrible's sing along blog. I highly recommend it. Not only does it have mad scientists, but it also has singing. So crazy. ‘Rules and models of the enemies of genius and art’, said William Hazlitt. So, everything I have told you this evening is wrong. If you can find a better way of doing it, okay? You have my permission to go and explore.

And lastly, you have my permission to be as creative as you like. Go out and live and enjoy. This is on our street and I just absolutely adore it.

And with that, on that bombshell. Thank you.

(Ending questions not transcribed, text edited for readability by Maddy Leslie)

.jpg?width=400&height=250&name=birmingham-museums-trust-ri8qLlGACc4-unsplash%20(1).jpg)